How Do Health Insurers Raise Costs, Reduce Access, and Lower Quality?

Case 1 -Episode 12 - Who Profits from Healthcare?

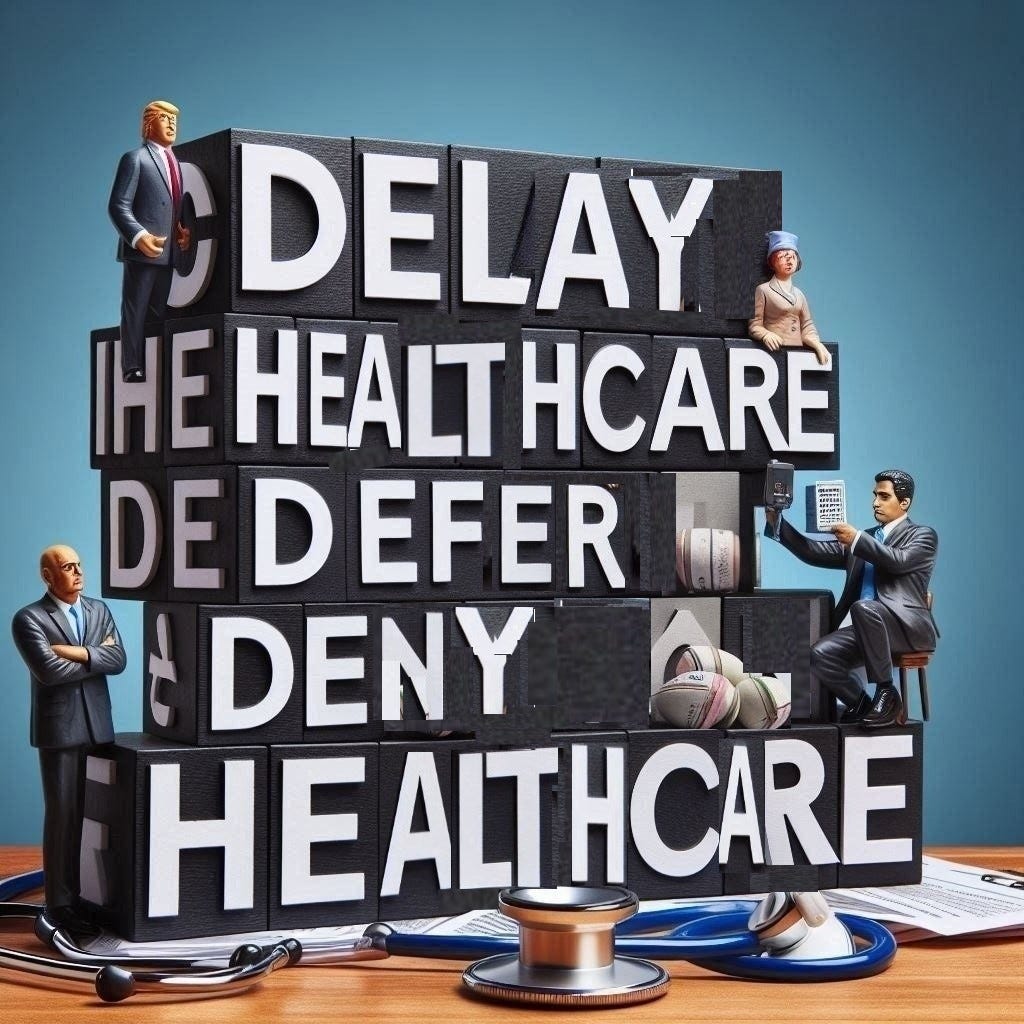

The three rules of health insurance companies is to: 1) delay care, 2) defer care, and 3) deny care. All three reduce costs and increase insurance company profits.

Insurers – Profit by Avoid Paying

Third party payers are either publicly traded for profit companies (i.e. UnitedHealth, Humana) or mutual companies. The latter is Blue Cross Blue Shield which is actually also for profit company but masquerades as a “non-profit” hidden by the 72,000 pages of the US Federal tax code. They all have a fundamental goal to make money. Insurers profit by paying out less for the services (codes billed) than they collect in insurance premiums from employers. They can accomplish that in several ways:

1) Limiting network size. By having a network of overworked providers, insurers can guarantee patients won’t be seen quickly, thereby delaying payment for services.

2) Rationing. By restricting access to certain medical services, they can delay or defer expensive ones. Requiring pre-authorization before a consultation is an example.

3) Paying providers less. An example is negotiating different rates with different providers.

4) Raise rates paid by employers on behalf of patients. Increasing copays is an illustration. High copays discourage patients from seeking medical care.

.

Limiting the Network

Insurance networks consist of doctors who agree to accept the payment rates set by insurance companies. The goal of insurance companies is to find providers willing to accept the lowest reimbursement. In areas with fewer insurance options, doctors face even lower compensation.

By limiting the number of doctors in their network, insurance companies can cut costs, as patients will face delays in getting appointments with providers who are overbooked and have limited availability.

Because primary care doctors within these networks are underpaid, they are required to see more patients, leading to schedules that are fully booked far in advance. As a result, they often lack the time to address more complex cases that they could otherwise handle if they had adequate time and resources. For example, family physicians are trained to manage minor skin surgeries, psychiatric patients with dual diagnoses, and basic orthopedic issues, but due to time constraints, they frequently refer these cases to specialists.

Ghost Networks of Nobody

Due to the low payment rates set by insurers, some specialty practices limit the number of insured patients they accept, leading to longer wait times for those seeking care. Over time, many specialists become frustrated with the inadequate reimbursement and choose to leave the insurance network altogether. Despite this, insurance companies often have little incentive to update their specialist lists, especially as they approach the time for signing up new customers.

This creates a misleading "ghost network," which appears comprehensive when patients enroll in the health plan but leaves them at risk when they can't access specialists when needed. As a result, specialists may move out-of-network, forcing patients to cover a larger portion of the costs. In some cases, insurance companies may design networks where specialists are located far from patients, making it even less likely they will receive timely care.

Rationing By Any Other Name

The insurance company often implements a pre-authorization requirement for many diagnostic procedures and tests, which further delays patient care. By combining pre-authorization hurdles with a limited number of specialists in the network, the insurer creates even more delays in treatment. Additionally, specialist networks typically come with higher co-pays, shifting more of the financial burden onto the patient. If the insurer can postpone care until the patient's coverage period ends, the responsibility for the costs may fall to the next insurance carrier.

Make Money by Paying Doctors Less

Health insurance pays healthcare providers directly, rather than having patients pay out of pocket. The system operates on a fee-for-service basis, where providers are compensated based on the specific services they perform, as outlined by procedure codes known as Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. The more CPT codes generated, the higher the total bill.

Insurers determine payments using a fee schedule tied to these codes. Each CPT code is assigned a value called Relative Value Units (RVUs), which quantify the amount of work involved in performing the procedure. The RVUs are multiplied by a negotiated dollar amount to establish the payment. These RVUs are set by representatives from various medical specialties under the American Medical Association (AMA). However, surgical specialties heavily outnumber non-surgical practitioners, such as internists, family doctors, and OB-GYNs, by a ratio of 17 to 1 on the AMA committee. As a result, technical (surgical) procedures tend to have much higher RVUs. Meanwhile, primary care physicians and others who perform cognitive tasks (diagnosis, patient consultations, etc.) are assigned significantly lower RVUs per unit of time.

Administrative tasks required for patient care, such as reviewing lab tests, patient education, reviewing consultations, and obtaining pre-authorizations, are generally not reimbursed at all in the fee-for-service system.

Over the past 20 years, certain medical specialties have diminished due to declining RVU rates. Specialties that involve more cognitive work have become harder to find. For example, rheumatology, once a common subspecialty with short wait times for appointments, has become much rarer. Rheumatologists treat over 125 immunologic diseases, which present with similar symptoms but require different treatments. Diagnosing these conditions requires extensive patient interaction and detailed examination. In the past, rheumatologists could offset the low RVU rates by billing for complex lab work. However, insurers began negotiating directly with labs, cutting out these payments. Now, wait times for a rheumatologist can be up to a year in some areas.

Neurology faces a similar decline. This specialty requires taking detailed patient histories and conducting thorough physical exams to identify subtle neurological signs that can differentiate between conditions with vastly different prognoses, such as fatal Lou Gehrig’s disease and treatable multiple sclerosis. Neurologists previously compensated for low RVUs by performing in-office neurological tests, but insurers now restrict reimbursement for these tests to certain settings, like hospitals. Like Rheumatologists, Neurologists are not available for many patients to receive care.

Other specialties, like Endocrinology, are also rapidly disappearing, and rural healthcare is becoming increasingly scarce. However, Dermatology presents a contrasting scenario. While it demands significant knowledge, like other fields, it doesn’t require extensive data gathering from patients since diagnoses are primarily visual. Documentation (physician use of electronic records) is minimal, often just a photograph, and much of skin care is not covered by insurance. As a result, Dermatology has thrived with the rise of “big health.” Nowadays, medical students are increasingly drawn to Dermatology residencies.1

Insurers continually reduce payments for each CPT code in an effort to save money. They often pay different rates to different providers for the same codes. Insurers may even offer financial incentives to patients to switch to doctors who accept lower payment rates. Large healthcare systems have more leverage in negotiations than small medical practices. If a major health system refuses an insurer's fee schedule, employers may choose another insurer if their employees cannot access local hospitals. Smaller practices, however, lack such bargaining power and merge with health systems. As a result, nearly 75% of doctors now work for health systems, which allows hospitals to create local monopolies and drive prices even higher.

Insurers Avoid Risk and Profit from the Government

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), enacted in 2008, was designed to provide health coverage to individuals with pre-existing conditions through government-supported insurance plans. Before its passage, health insurers could "cherry-pick" healthy individuals who posed less financial risk, while denying coverage to those with chronic illnesses that could lead to higher costs. Public demand for change led to the legislation, which narrowly avoided repeal in 2017 by a single vote.

The ACA allows insurance companies to earn a profit for administering Federal Health Insurance Marketplace plans. It ensures coverage for individuals who might have been rejected by private insurers due to pre-existing conditions. Profits for Medicaid administration are typically set at 15%, while profits for private healthcare plans can reach up to 18%. There are constant calls to repeal ACA by the health insurance lobby.

Let the Patient Pay More

Insurance companies charge premiums to employers to cover healthcare costs for their employees. If the previous year's healthcare expenses don't meet the insurer's profit goals, they simply raise the rates to maintain profits. Employers, in turn, can either absorb the cost increase, self-insure, or pass the financial burden onto employees through higher copays and deductibles. These cost structures are often intentionally complex, reducing the employer’s share of healthcare expenses while increasing the employee’s share.

Preserve Profits, Not Improve Quality

Insurers, however, have no financial incentive to prioritize quality of care or patient outcomes. Their focus is on ensuring that some provider sees the patient, not necessarily on the quality of the medical treatment provided. By relentlessly cutting fees, insurers make doctors spend less time with patients. As a result, insurers do not prioritize improving healthcare outcomes. As one insurance executive told me, “Dr. Wenner, we pay you to see the patient. If you want to practice quality medicine, do it on your own time.” Health systems function as designed.

Opinion

Traditional Medicare has allowed patients to choose their care options freely. However, patients might opt for insurance restrictions in exchange for lower out-of-pocket costs through private insurance plans. These Medicare Advantage Plans offer additional benefits like eye care, dental cleanings, gym memberships, and even free food. However, these plans offer these “free services” to limit access to expensive, life-saving treatments with complex prior authorization rules and unexpected coverage gaps, resulting in delays, deferrals, and denials of care.

Dr. Mehmet Oz, the incoming head of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (Medicare), favors mandatory privatization through Medicare Advantage. This shift will have significant implications for patients needing specialized care. Medicare recipients should be aware that this rationing may result in barriers to accessing care outside the “network” or receiving advanced treatments. The process could require months of applications and pre-authorization paperwork, all handled via snail mail. With a 3% increase in mortality per week, the privatization of Medicare will impact patient outcomes, as discussed in the importance of Time to Treatment in Episode 9.

Patient Action

Preview

Next we will analyze what might have happened if the the patient’s care in Case #1 had been centered on the patient instead of the system. We will explore health care as individualized care for better health rather than sick care centering on illness treatment.